John Mathias Barnard (1875-1945) (52 Ancestors #17) Theme: "Prosper"

The person who immediately springs to mind in the context of a success story is my grandfather-in-law John Mathias Barnard, my husband's paternal grandfather. When John was just four, the sudden death of his father threw the family from apparent comfort into poverty. His ambition, character, personality, good looks and innate ability enabled him to work his way up in society and to prosper.

|

| 1901 wedding photo of John Mathias Barnard and Florence Hacon |

|

| John Mathias Barnard and wife Florence Hacon Probably in front of The Maples, Oulton Broad, Lowestoft |

Roots in the Forest of Dean

John also forms a link in the R-L625 [2020 update: revised name is R-L21, subclade R-DF5]haplogroup Y chromosome chain that has been passed down the generations to my husband and other Barnard men in this family. This Y chromosome haplogroup is often found in Ireland and the western part of England, exactly where the Barnards were found back as far as I have been able to trace: my husband's 3X great grandfather Thomas Barnard (1771-1848) who lived on Plump Hill in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England. This old forest area is very near Wales and is almost a triangular island, surrounded on two sides by the Severn and Wye Rivers and on the other by Herefordshire.

The Forest of Dean is unique in many ways, one of the most significant for this story being the system of coal and iron mine ownership and regulation known as freemining. This system has been in place for centuries and exists to the present day. Traditionally, any male over the age of 21 born in the Hundred of St Briavels who worked a mine for a period of one year plus one day would obtain the personal right to mine that claim as a Free Miner. The Dean Forest Mines Act of 1838 confirmed these freeminers' rights, but also allowed them to pass on title to their claims or "gales" to outsiders. Freemining rights can also include quarries - something that was also to prove useful to the Barnards.

The Forest of Dean has its own dialect, sometimes called by the locals "speaking Forest" (and watch for this to pop up again later in this story).

Another story that has been passed down in the family is that Emma was somehow deprived of most of the assets that James had held, probably including his freemining rights. (It isn't clear whether Emma as a female would simply not have been entitled to retain those rights and her oldest son Job would not have yet attained the required 21 years of age at the time of his father's death. Perhaps James had had a partner or relative whose legal right took priority. Or perhaps there was skulduggery. In any event, based on comments made later by her son John, he clearly felt that women were taken advantage of in business and this undoubtedly came from the bad experience his mother had had as a widow.)

James had probably been a good provider. He kept a butcher shop as well as being a quarry man and builder of houses. He built the first brick house on Plump Hill, called, appropriately enough "Brick House".

James was an innkeeper at the "Butcher's Arms" at the time of the 1861 British census and an iron miner at the time of the 1871 British census. In 1875 he had taken over Birch Hill Folly gales with Reuben Joynes and is listed in the 1875 census as being a mine overman (probably because of these freemining rights), but by 1879 there is no evidence of such rights persisting.

The older boys were also making a contribution to the family's upkeep, but the situation could not have been an easy one. Job at 20 was working as a gardener. By the time Naboth was 10 years old, he was working in a mine as a pit boy. Child labour was common, especially in the mines. There is no indication that John ever worked in the mines but he did contribute to the family's upkeep. At the age of 9, he picked rocks for 6 pence a day. He and brother Naboth collected laundry from families up to 2 miles into the forest for his mother to launder for 1 penny plus 1 penny carriage. At the age of about 10, he was sent to London to be an errand boy for an uncle. He was a page boy in an ice cream stall and an errand boy for a butcher. Earning just 3 shillings 6 pence a week, he still managed to send 2 shillings 6 pence home to his mother.

My husband recalls stories his grandfather John related to him, but it is difficult to pinpoint a date or details for this. Apparently John was falsely accused of stealing a shilling from an uncle and was imprisoned in a cellar of the house from which he made his escape. He also told him of having walked to Lowestoft from London.

By the time he was 15, he was a full-fledged butcher as shown by the 1891 British census:

His last service post was as head butler in the Hanbury household at Herbert House, Belgrave Square, London. In a letter dated 8 February (probably 1899), John proposed to Florence to clarify his seemingly awkward attempt in person of the previous evening. The Hanburys and their household spent time at Ilham Hall, Ashbourne, Darbyshire from which John wrote many letters on Ilam Hall stationery to his "own dear Florrie". His departure from this position was an unexpected one. In a letter to Florence dated June 7th (or possibly 27th, no year stated), after starting the letter with pleasantries, he says, almost as an afterthought: "I am sorry to tell you that Mrs Hanbury discharged me this morning. I am to leave this day month. I feel it very much to think that I gave my own notice twice and they begged of me to stop with them and directly all the company went this morning she asked to see me and it came like a thunderbolt for only last Wednesday week she promised to do great things for me and asked me to stay until Mr. Hanbury could get me something out of service." Two other servants were discharged at the same time. His parting thought was "I suppose it is all for the best" - he was clearly trying to make a change in their circumstances so that he and Florence could marry. Living amidst wealth and power probably gave him the motivation to prosper himself.

There is also some correspondence from the Royal National Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest, Vendun on the Isle of Wight where he was recovering from rheumatic fever just after Christmas one year. (I really wish he would have put the full dates on his letters, but I'm sure he wasn't thinking about snoopy family historians trying to fit together the pieces a century later!)

John was not part of either of the Newton or Hanbury households when the 1901 census was conducted on 31 March 1901. Lord and Lady Newton and their 3 daughters were enumerated, along with some 16 servants including 25 year-old lady's maid Florence. By then, John had moved to Lowestoft and had set himself up with a butchering business; he was a boarder at 11 Factory Street in the home of his future mother-in-law, Elizabeth Hacon. A month after the census, John wrote to Florence advising her that a second butcher shop was for sale on Crown Street and thinking that he should buy it to increase their business; he didn't have the full amount of the payment and asked if she would contribute 30 pounds which she obviously did since his business stationery later had both addresses on it. The couple were married in the summer of 1901.

During the First World War, John sent Florence and their children (sons John and Arthur and daughters Florence, Winnifred and Beatrice) to live with his brother Job and family in the Forest of Dean. This was much farther away from the action and felt to be much safer. Florence had been badly frightened by the German zeppelins that had been coming over Suffolk. The letters that he wrote to her during their separation show how deeply he loved her and their children and how much he missed them. Like all his letters to her both before and after their marriage, he never tells her what to do but says she must do what she thinks best. For awhile, he thought he would enlist in the military to do his duty and dull his pain from the separation, notwithstanding his rheumatic heart and his age by now approaching 40.

It is likely during this separation in 1915 that he wrote her a lengthy letter clarifying his wishes "in the event of my death (I think at this crisis every man should be at least ready for the sake of his loved ones and his country)" and providing her with guidance as to "how to deal with our property although I advise you I want you to understand you are perfectly free to act as you think fit." He discouraged her from continuing in the butchering business, saying, "As you know, females can be robbed right and left." Later he says, "I want you to get hold of every possible shilling that belongs to you and ours. If at times I appear to you to have been mean I wish you to know that my whole life one ambition has been to benefit you and ours at this time therefore I trust you will carry out my wish and compel every debtor to pay up. It is only what you and I have worked hard for, and once again I entreat you to look out for the rainy day as I know from my young life how little ones are left in the lurch and done out of their own and I know your generous nature, hence my special appeal to you now and I want you to act while there is time as there are so few that will give you what belongs to you unless you demand it." (These comments obviously result from how his mother had been left destitute after her husband's death.). The properties that he mentions in this letter include 8 Suffolk Road and 39 Crown Street, Oulton Street, Beccles Road and the Carlton Colville marshes.

He closes the 24 July letter with the following: "Warn our dear boys of the dangers that beset them. I know you will do your part with the dear girls but I ask you to do my part to the boys, teach them of our Love and happiness and of the enormous importance of being Truthful tell them this is Daddy's great wish that they should above all be Truthful as this is the foundation for their future."

Florence and the children did return to Lowestoft for the remainder of the war; John did not enlist. Several of the Slater and Barnard fishing trawlers were destroyed during the war. The Trevone, a 46 ton fishing smack owned by John was sunk by the German U-boat U 55 Wilhem Werner on 30 January 1917 off the west coast of England 30 miles NW of Trevose Head with two casualties.

From 1923 to 1925 John served as mayor of Lowestoft, Suffolk, England.

One gets a sense that he regarded this as a civic duty and a position in which he could make a difference. For example, supporting the local hospital was important to him and he sponsored a Christmas variety "Programme of Entertainments supporting the Mayor's Appeal for the Hospital" that included events scheduled over a full week in December of 1924.

Much of the time he was expected to represent Lowestoft at social events. The picture below contains just 4 of the dozens of events he would have attended during his mayoralty.

Another time an invitation was sent from Lady Somerleyton to Florence as Mayoress, inviting them to supper at Somerleyton Hall with Prime Minister Baldwin.

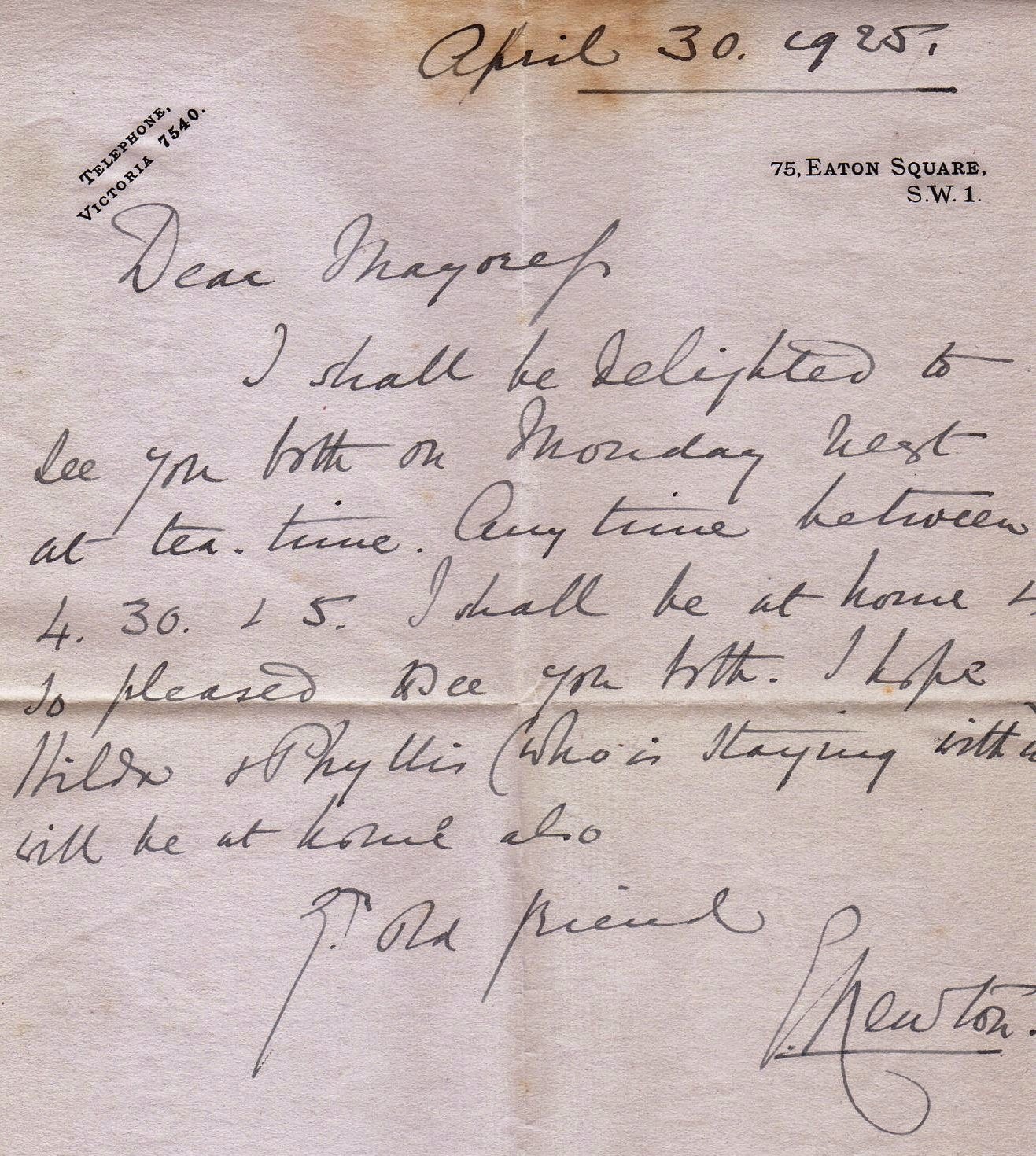

During his term as Mayor, Lady Newton also invited them both to tea when they visited London. In this and other letters, Lady Newton refers to her friendship for Florence who had once been her lady's maid.

He continued to serve as an alderman in Lowestoft for many years after his terms as mayor.

One of his many homes was Wissett Lodge near Halesworth, Suffolk. My husband's father (also John Barnard) had died suddenly of blood poisoning at the age of 35 on 19 December 1943. As if this hadn't created enough tragedy and turmoil for the family, just a couple of nights later a British Lancaster bomber crashed in a field behind Wissett Lodge on a return flight from Germany. Damaged and unable to deploy its bombs on its mission, it created a major impact that blew in the windows in the house. My husband was in the upstairs right-hand bedroom asleep when it happened and he remembers his mother and grandmother Florence coming to rescue him and cutting their feet in the broken glass. To say that this was a hugely stressful time for John would be an understatement.

|

| Plump Hill in the Forest of Dean 2004 |

The Forest of Dean is unique in many ways, one of the most significant for this story being the system of coal and iron mine ownership and regulation known as freemining. This system has been in place for centuries and exists to the present day. Traditionally, any male over the age of 21 born in the Hundred of St Briavels who worked a mine for a period of one year plus one day would obtain the personal right to mine that claim as a Free Miner. The Dean Forest Mines Act of 1838 confirmed these freeminers' rights, but also allowed them to pass on title to their claims or "gales" to outsiders. Freemining rights can also include quarries - something that was also to prove useful to the Barnards.

The Forest of Dean has its own dialect, sometimes called by the locals "speaking Forest" (and watch for this to pop up again later in this story).

|

| Birth Record for John Mathias Barnard 11 December 1875, Plump, East Dean, Gloucestershire |

Death of Father Changes Everything

John Mathias Barnard was born to James Barnard and his wife Emma Smith on 11 December 1875 at East Dean in the Forest of Dean. His parents already had 7 children by the time he arrived: Job born 1861, George 1863, Matilda 1865, Mary Jane 1867, Theophilus 1870, Flora 1872 and Naboth 1873. They had lost eldest son Clement at the age of 16 just the year before John was born. One additional son Arthur would complete the family in 1879, the same year that father James died at the age of 46, leaving Emma widowed at age 41 with 9 children to feed and clothe. The family story was that James was considered the strongest man in the Forest of Dean and had accepted a wager that had him hauling two 120 pound bags of corn up a very steep grassy hill; he had injured himself so badly that he had never been able to lie down again. This rupture might well have been the cause of his early death.Another story that has been passed down in the family is that Emma was somehow deprived of most of the assets that James had held, probably including his freemining rights. (It isn't clear whether Emma as a female would simply not have been entitled to retain those rights and her oldest son Job would not have yet attained the required 21 years of age at the time of his father's death. Perhaps James had had a partner or relative whose legal right took priority. Or perhaps there was skulduggery. In any event, based on comments made later by her son John, he clearly felt that women were taken advantage of in business and this undoubtedly came from the bad experience his mother had had as a widow.)

James had probably been a good provider. He kept a butcher shop as well as being a quarry man and builder of houses. He built the first brick house on Plump Hill, called, appropriately enough "Brick House".

|

| Back of Brick House (front has been resurfaced, but this part is original), Plump Hill, Gloucestershire 2004 |

James was an innkeeper at the "Butcher's Arms" at the time of the 1861 British census and an iron miner at the time of the 1871 British census. In 1875 he had taken over Birch Hill Folly gales with Reuben Joynes and is listed in the 1875 census as being a mine overman (probably because of these freemining rights), but by 1879 there is no evidence of such rights persisting.

Scraping By

James's unexpected death left Emma destitute. Too proud to allow herself and her children to fall under the Poor Law and end up in a workhouse, Emma turned to shopkeeping and taking in boarders and ironing to make a living. |

| 1881 British census for East dean, Westbury on Severn, page 18 |

The older boys were also making a contribution to the family's upkeep, but the situation could not have been an easy one. Job at 20 was working as a gardener. By the time Naboth was 10 years old, he was working in a mine as a pit boy. Child labour was common, especially in the mines. There is no indication that John ever worked in the mines but he did contribute to the family's upkeep. At the age of 9, he picked rocks for 6 pence a day. He and brother Naboth collected laundry from families up to 2 miles into the forest for his mother to launder for 1 penny plus 1 penny carriage. At the age of about 10, he was sent to London to be an errand boy for an uncle. He was a page boy in an ice cream stall and an errand boy for a butcher. Earning just 3 shillings 6 pence a week, he still managed to send 2 shillings 6 pence home to his mother.

My husband recalls stories his grandfather John related to him, but it is difficult to pinpoint a date or details for this. Apparently John was falsely accused of stealing a shilling from an uncle and was imprisoned in a cellar of the house from which he made his escape. He also told him of having walked to Lowestoft from London.

By the time he was 15, he was a full-fledged butcher as shown by the 1891 British census:

|

| 1891 British Census for Westminster (London) |

Domestic Service

He then decided to enter domestic service, working his way up to be head footman for Lord Newton. The role of footman was largely a decorative one to display the prestige of the employer, and tall handsome young John would have fit the bill perfectly. Lord Newton's family seat was at Lyme Park, Derbyshire - the mansion that stood in for "Pemberley" in the BBC production of "Pride and Prejudice". But it was undoubtedly in the Newton household in Belgravia, London, that John met his future wife, Florence Hacon from Lowestoft who was lady's maid to Lady Newton. (Shades of "Downton Abbey"!) John wrote to Florence while she was staying at Lyme Park with the Newtons. (In most letters, he calls her "Florrie" and signs his name "Jack".) Their courtship would seem to have lasted for some 5 years.His last service post was as head butler in the Hanbury household at Herbert House, Belgrave Square, London. In a letter dated 8 February (probably 1899), John proposed to Florence to clarify his seemingly awkward attempt in person of the previous evening. The Hanburys and their household spent time at Ilham Hall, Ashbourne, Darbyshire from which John wrote many letters on Ilam Hall stationery to his "own dear Florrie". His departure from this position was an unexpected one. In a letter to Florence dated June 7th (or possibly 27th, no year stated), after starting the letter with pleasantries, he says, almost as an afterthought: "I am sorry to tell you that Mrs Hanbury discharged me this morning. I am to leave this day month. I feel it very much to think that I gave my own notice twice and they begged of me to stop with them and directly all the company went this morning she asked to see me and it came like a thunderbolt for only last Wednesday week she promised to do great things for me and asked me to stay until Mr. Hanbury could get me something out of service." Two other servants were discharged at the same time. His parting thought was "I suppose it is all for the best" - he was clearly trying to make a change in their circumstances so that he and Florence could marry. Living amidst wealth and power probably gave him the motivation to prosper himself.

Health Problems

The story is told that one day he was trying to carry a bucket in one hand and salute his master with the other while riding a penny farthing. (The timing of this story isn't clear; it cannot be said with certainty whether this was during his time in the Newton household or in the Hanbury household.) In any event, he fell and was so badly injured that he nearly died. He had a weak heart having suffered several bouts of rheumatic fever. The first part of his convalescence was spent at Royden Hall, Tonbridge, Kent, but then he was ordered to have a full month's complete rest so he went back home to the Forest of Dean.There is also some correspondence from the Royal National Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest, Vendun on the Isle of Wight where he was recovering from rheumatic fever just after Christmas one year. (I really wish he would have put the full dates on his letters, but I'm sure he wasn't thinking about snoopy family historians trying to fit together the pieces a century later!)

Setting Up His Own Business and Home

At some point he bought a carrier's business. However, this business seems to have been short-lived since his fiance didn't think that was a suitable job for him.John was not part of either of the Newton or Hanbury households when the 1901 census was conducted on 31 March 1901. Lord and Lady Newton and their 3 daughters were enumerated, along with some 16 servants including 25 year-old lady's maid Florence. By then, John had moved to Lowestoft and had set himself up with a butchering business; he was a boarder at 11 Factory Street in the home of his future mother-in-law, Elizabeth Hacon. A month after the census, John wrote to Florence advising her that a second butcher shop was for sale on Crown Street and thinking that he should buy it to increase their business; he didn't have the full amount of the payment and asked if she would contribute 30 pounds which she obviously did since his business stationery later had both addresses on it. The couple were married in the summer of 1901.

Prosperity Arrives - and so does War

Business prospered, and he partnered with a man named Jonathan Slater in trawl fishing. They owned at least 24 trawlers including two that remain afloat today - Sunbeam and Deodar. The profits were invested in buildings, farms and marshes. He had gone into house building as well, often incorporating the name "dean" into the house name in honour of his home in the Forest of Dean.During the First World War, John sent Florence and their children (sons John and Arthur and daughters Florence, Winnifred and Beatrice) to live with his brother Job and family in the Forest of Dean. This was much farther away from the action and felt to be much safer. Florence had been badly frightened by the German zeppelins that had been coming over Suffolk. The letters that he wrote to her during their separation show how deeply he loved her and their children and how much he missed them. Like all his letters to her both before and after their marriage, he never tells her what to do but says she must do what she thinks best. For awhile, he thought he would enlist in the military to do his duty and dull his pain from the separation, notwithstanding his rheumatic heart and his age by now approaching 40.

It is likely during this separation in 1915 that he wrote her a lengthy letter clarifying his wishes "in the event of my death (I think at this crisis every man should be at least ready for the sake of his loved ones and his country)" and providing her with guidance as to "how to deal with our property although I advise you I want you to understand you are perfectly free to act as you think fit." He discouraged her from continuing in the butchering business, saying, "As you know, females can be robbed right and left." Later he says, "I want you to get hold of every possible shilling that belongs to you and ours. If at times I appear to you to have been mean I wish you to know that my whole life one ambition has been to benefit you and ours at this time therefore I trust you will carry out my wish and compel every debtor to pay up. It is only what you and I have worked hard for, and once again I entreat you to look out for the rainy day as I know from my young life how little ones are left in the lurch and done out of their own and I know your generous nature, hence my special appeal to you now and I want you to act while there is time as there are so few that will give you what belongs to you unless you demand it." (These comments obviously result from how his mother had been left destitute after her husband's death.). The properties that he mentions in this letter include 8 Suffolk Road and 39 Crown Street, Oulton Street, Beccles Road and the Carlton Colville marshes.

He closes the 24 July letter with the following: "Warn our dear boys of the dangers that beset them. I know you will do your part with the dear girls but I ask you to do my part to the boys, teach them of our Love and happiness and of the enormous importance of being Truthful tell them this is Daddy's great wish that they should above all be Truthful as this is the foundation for their future."

Florence and the children did return to Lowestoft for the remainder of the war; John did not enlist. Several of the Slater and Barnard fishing trawlers were destroyed during the war. The Trevone, a 46 ton fishing smack owned by John was sunk by the German U-boat U 55 Wilhem Werner on 30 January 1917 off the west coast of England 30 miles NW of Trevose Head with two casualties.

Mayor of Lowestoft

|

| John M Barnard, Mayor of Lowestoft in foreground At the War Memorial, the Plain, Lowestoft 1924 |

One gets a sense that he regarded this as a civic duty and a position in which he could make a difference. For example, supporting the local hospital was important to him and he sponsored a Christmas variety "Programme of Entertainments supporting the Mayor's Appeal for the Hospital" that included events scheduled over a full week in December of 1924.

Much of the time he was expected to represent Lowestoft at social events. The picture below contains just 4 of the dozens of events he would have attended during his mayoralty.

|

| A few of the invitations for John and Florence as Mayor and Mayoress of Lowestoft |

Another time an invitation was sent from Lady Somerleyton to Florence as Mayoress, inviting them to supper at Somerleyton Hall with Prime Minister Baldwin.

During his term as Mayor, Lady Newton also invited them both to tea when they visited London. In this and other letters, Lady Newton refers to her friendship for Florence who had once been her lady's maid.

The Good Life - but War Arrives Again

John clearly appreciated the good life that his hard work had produced. He enjoyed boating and picnicking with family and took obvious pleasure in the vehicle and company in this picture. His brother Arthur George Barnard had gone to Australia and prospered greatly there; this picture is believed to be of the two brothers shortly before Arthur George's death. |

| John second from left and Florence third from left c. 1927 |

|

| Wissett Lodge, Halesworth, Suffolk |

Final Days

He moved to Saxtead Green, Suffolk, to retire but died just 6 weeks into his retirement in January of 1945 (co-incidentally the same month that my paternal grandfather died half a world away). He and Florence were staying with daughter Winnifred and her husband Joe Smith at Pond Farm, Suffolk, at the time. My husband was a young child living with the Smiths and remembers that day well. There had been a draft through one of the lead-paned windows and John had got up from his death-bed to repair it, much to the surprise and shock of all the adults in the family. Shortly before he died, my husband was most amazed to hear his grandfather speak in a foreign language that he had never heard before - we now think that he was "speaking Forest" harking back to his childhood in the Forest of Dean.Obituary and Burial

An update to how we located the obituary and grave sites of John and Florence can be located here.

Sources:

- Barnard, Richard, "My Family History" school genealogy project based on information provided in the 1970's by Arthur Barnard, son of John Matthias Barnard

- British Censuses for 1841, 1851, 1861, 1881, 1891, 1901

- National Geographic Genographic Project DNA analysis dated 06 January 2013

- Personal memories and original handwritten photographs, letters and memorabilia in possession of Graham Barnard

- uboat.net website for "Ships hit during WWI", Trevone, accessed 26 April 2015

Labels: 52 Ancestors 2015, Barnard

.jpg)